During summer 2024 I traveled with family on a month-long study trip to Greece. I wanted to see the ancient sites with their art treasures and better understand the context and life of Greek people, and how it shaped their art and still shapes their worldview today. After reading so many texts and listening to so many lectures about the primacy of Greece in Western civilization, I finally had a chance to see it up close.

My Reading List

For about three months prior to our departure, I geared my regular reading to focus on Ancient Greece. I reviewed several of my favorite books and picked up Tom Holland’s very enjoyable 2014 translation of Herodotus.

Among the books I used to brush up were surveys including Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way and Mythology – both easy reading for a general audience. I also spent some time with Will Durant’s The Life of Greece, Donald Kagan’s Ancient Greek History lectures at Yale (an excellent free resource on YouTube), several plays, including a dramatization of The Oresteia, and for contrast, both Aristophanes The Clouds and Plato’s Apology. Gregory R. Crane’s Perseus Digital Library with Tufts University was also a constant companion when delving into mythology and symbolism.

In addition to Blue Guides for travel recommendations, I also picked up a modern Greek phrasebook to read on the flight, and a little treat for myself: Ancient Greek Architects at Work: Problems of Structure and Design.

Though my primary interest is art history, I limited my intake of art history texts, as I expected the museums and sites to be texts unto themselves. I still spent a few evenings with Richard Brilliant’s Arts of the Ancient Greeks, and a couple of John Boardman’s catalogs of vases. I also made two separate visits to The Metropolitan Museum here in New York with Boardman in hand to see some of the highlights with the help of his organization to better identify styles and periods, if not individual artists.

Since we were staying the first few nights in Athens to do more conventional sites with family, I would have time to plan our other excursions once in Greece and perhaps enjoy the advice of locals. However, with little prior knowledge of the geography, I decided to reserve time before our departure to compile a priority list of ancient sites and correlate them with modern place names. I was expecting the difficulty of charting Odysseus’ voyage.

However, we were not island hopping the entire Aegean, but rather staying mostly on the mainland. The only initial hurdle was the shift in spelling from English to Greek (with a smattering of Italian for flavor). After a little concentration this proved fairly straightforward. With the exception of Epidaurus, I was pleasantly surprised to see that almost every ancient site is in immediate proximity to the modern town of the same name.

Planning and Preparing

Our initial itinerary for the first week and a half included three nights in Athens, an overnight stay at Delphi and two nights on Santorini, then three nights back in Athens.

Later, my wife and daughter and I would take a few excursions, including a car trip in the Peloponnese to see sites from ancient Argolis, Sparta, and Olympia.

Little did we know that a heat wave would hit Athens, and our itinerary would change, taking us to a beautiful destination on the spur-of-the-moment that proved to be one of the most relaxing and fun excursions of our entire trip.

In between these journeys farther afield, I made it my mission to see as many archaeological sites within Athens as possible. Going off the beaten track proved fruitful, and we met many friendly, welcoming people who were eager to share their favorite activities and give us deeper insight into the layers of culture and history everywhere we went.

The following accounts and images are roughly chronological except that I have grouped for the sake of clarity some of the sites in Athens which in fact took place between other excursions.

Our home away from home for the month was a charming two-bedroom apartment in Thiseio, just on the other side of Philopappos Hill. Tucked into a family neighborhood away from the bustle, crowds, and nightlife, yet a short walk to the foot of the Acropolis, it proved ideal for our family. It had a front garden with lemon trees, a hammock, and a porch with an outdoor dining table. Nothing extravagant, humbly appointed, but comfortable and close to everything we wanted to see and do.

The excitement of staying in Greece got us up before dawn the first morning, and this became our daily ritual. Since we had several weeks, it made sense to pace ourselves and adapt to the habits that would maximize our use of energy and opportunity. We adopted a fairly consistent schedule. We planned each day around seeing at least one site or museum. If we were able, we got up around 5am to paint the sunrise. After that, for days with morning sightseeing, we had a quick breakfast where we were staying and arrived at the site at opening time, making the most of the morning until the heat became intense. After lunch, we would siesta and then go out again in the late afternoon and stay out until around 10pm.

Alternatively, if the site was an indoor museum, we might delay the siesta and spend the late morning and early afternoon enjoying the climate controlled rooms, then rest from mid-afternoon until close to dusk, and have a late dinner.

This is how we often found ourselves walking the opposite way of large crowds of sunbaked tourists, stayed out of the hottest weather, enjoyed both the beauty, quiet, and cool of the city just waking up, and found the relaxed pace of a slow dinner and leisurely strolls through the buzz and energy of the streets at night. We were quite active, yet the days felt like leisure.

Philopappos Hill and The Acropolis

My wife seems to be less susceptible to jet lag than I, so she had been painting for nearly an hour on Philopappos Hill that first morning when I arrived. That particular view of the Acropolis would become fixed in my mind as we would visit many more mornings. After the sun rose fully, we climbed back down the hill to meet the rest of our family. It would be a couple of days before I realized how close our painting spot was to an important landmark: the Pnyx, where democratic debate was born and the great questions of classical Greece were flogged out in full sight of the sacred hilltop we would visit later that very day.

We had booked our Acropolis entry time before we even left the US. We estimated as a family that two hours would be sufficient, so we chose a time later in the day to avoid the heat and the crowds. The site was still quite busy, but we didn’t feel pressed. I decided to come back a second time for the theaters located on the slopes of the hill.

The bad news first: In some ways, the Acropolis is better from a distance. While it is perhaps the most recognized icon of Western civilization, its prominence is more as a symbol than an actual place. The level of destruction of the actual buildings is profound, and most of the artifacts have been sheltered in the Acropolis Museum which we will treat at length below.

This is a theme that runs throughout this article, but do not be discouraged. On the bright side, experiencing the ancient sites of Greece is a rich experience that rewards scholarship and imagination. This holds an important lesson for anyone who wants to travel to see historic sites. The level of destruction or decay is as variable as can be imagined, and reaching some understanding from the fragments is not always so straightforward. That is the very reason why archaeology, anthropology, and art history matter so much – to give the world a better view on the past and to celebrate the achievements and splendor of cultures that differ in time and place from our own. The scavenger hunt I planned for my daughter was really an extension of how I view doing my own study. It is a great joy to see pieces fall into place – when the puzzle comes together it can be surprising and change the way we see the world and even ourselves. Many times in my travels, the brilliance and dedication of people working in these fields have enriched my experience and understanding beyond words.

There are two entrances for the Acropolis, and we chose the one for the Propylaea. The approach is along the broad pedestrian boulevard Apostolo Pavlou, and the hillside is maintained as an attractive public park. Right away you get a profound sense of the arid climate and rugged terrain. The pathways alone tell you this is a major site, yet the numerous trees along the path keeps the destination partially hidden from view. After slowly gaining altitude, the path suddenly becomes stairs and climbs rapidly, switching back and forth over broken remnants of what is believed to have been a long, continuous ramp designed to facilitate the driving of sacrificial cattle to the summit. The grand ascent up a steep slope to a holy place for sacrifice is reminiscent of so many ancient cultures. If the ramp was still intact today, the experience would be similar to sites like Chicken Itza, Ek Balam, and Monte Alban in Mesoamerica, albeit without individual steps. The prominence, public visibility, and literal elevation of the site would have marked the place as sacrosanct to all who saw it.

While we today consider the Parthenon as the most beautiful, iconic, and important structure, it was the Propylaea and the statue of Athena that garnered more attention in ancient sources. This is because when it was intact, the great gates dominated the view from the ground. The perspective of the ramp drawing you upward created a focal point on the huge structure immediately at the top of your ascent. The scale and prominence of the different structures on the Acropolis did not correspond to their sanctity, however.

The huge outdoor Athena Promachos was famous in the ancient world because of its role as a beacon – the shining tip of her spear could be seen at the Port of Piraeus about five miles away. By contrast, it was not the sacred statue at the focus of the most important civic ceremony in honor of Athena. Rather, an olive wood statue of Athena Polias, believed to have fallen from heaven, was the focus of the Panathenaic Procession and the recipient of the new peplos woven and presented each year in an elaborate public spectacle. It was housed first in the old temple of Athena and later, it or its replacement were housed in the Erectheon, Thus the Parthenon was never the primary focus of the Panathenaic Procession.

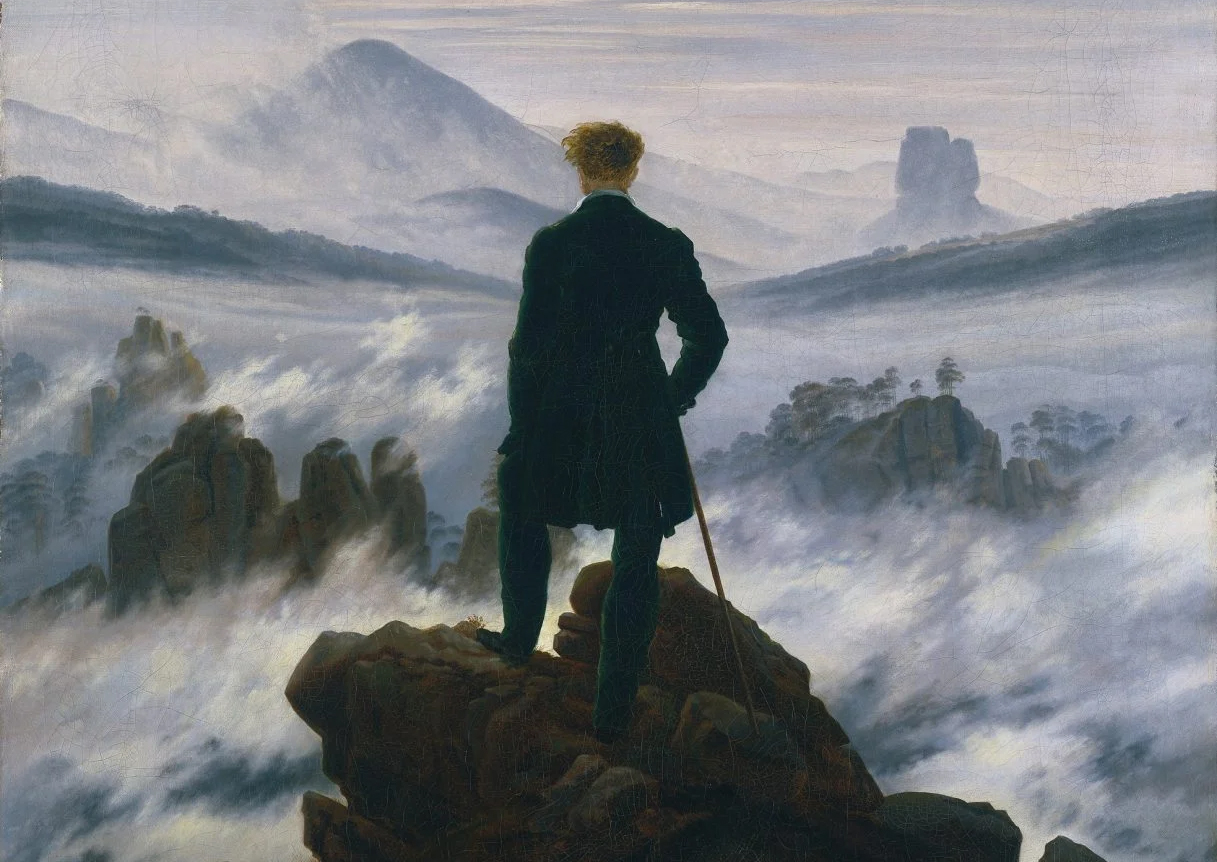

The most enriching part of being at the site was to experience something of its planning and formal arrangement. There is no substitute for understanding a location with its scale, light quality, and place in the landscape than to stand on the very spot. In the course of writing this, I realized that my earliest memory of the power of a place was at the age of four at Gettysburg. My first glimpse of the battlefield was at dawn on a foggy morning in October, and I was convinced that the ghosts of the soldiers were there. I climbed a watchtower and looked out, fully expecting to see an army advancing through the mist.

The Acropolis must have held those kinds of memories for the classical Athenians. The Parthenon was completed while the sack of the Acropolis by the Persians was still in living memory, and a few of the remnants of the older structures were used to rebuild the new. Moving the treasury of the Delian League must have been an incredible relief for the Athenian people as well as its leaders. Not only did it fund new and splendid civic structures, it restored splendor to the sacred site – it is understandable that they saw it as a justifiable use for the funds collected for the Delian League. Since the enemy of the League had destroyed the Acropolis, the common defense fund could also be used to recover from the damage that enemy had caused. Athenians could proudly point to the magnificent new site as something worth defending, galvanizing support for the mutual defense.

Their aspirations are reminiscent of a passage in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night:

See that little stream — we could walk to it in two minutes. It took the British a month to walk to it — a whole empire walking very slowly, dying in front and pushing forward behind. And another empire walked very slowly backward a few inches a day, leaving the dead like a million bloody rugs. No Europeans will ever do that again in this generation…

This took religion and years of plenty and tremendous sureties and the exact relation that existed between the classes. The Russians and Italians weren’t any good on this front. You had to have a whole-souled sentimental equipment going back further than you could remember. You had to remember Christmas, and postcards of the Crown Prince and his fiancée, and little cafés in Valence and beer gardens in Unter den Linden and weddings at the mairie, and going to the Derby, and your grandfather’s whiskers…

This kind of battle was invented by Lewis Carroll and Jules Verne and whoever wrote Undine, and country deacons bowling and marraines in Marseilles and girls seduced in the back lanes of Wurtemburg and Westphalia. Why, this was a love battle — there was a century of middle-class love spent here. This was the last love battle.

Modern Greece, too, glitters with examples of national pride, including the myth of Konstantinos Koukidis and the real-life Manolis Glezos and Apostolos Santas who galvanized resistance to occupation by fascist forces in World War II.

When you see the color guard procession on the Acropolis at sunrise and again at dusk, when you see the names that adorn the public monuments and buildings, and when you see the care and attention that goes into preserving their landmarks, you feel the pride of modern Greece.

The experience of standing on the Acropolis gives both a profound sense of importance but also emptiness. Fortunately, most of the treasures of the site are housed in a museum with the space and design sensibilities to fill the void. It also brings to mind the burning question: when will the Elgin Marbles return?

While I believe that Greece as it is today should be able to repatriate its treasures, especially the Elgin marbles, the simple answer that repatriation is always right is problematic. On one side, it would be ideal that the patrimony of a nation’s material treasures and artifacts should be within that nation’s control, if not even more specifically within that specific culture’s control. The US has plenty of its own issues on that front, both with artifacts from foreign and domestic soil, not to speak of the soil itself.

The other side is perhaps best exemplified in recent memory by the tragedy of the Cyrene Venus. Italian authorities may have felt justified in allowing its return to the country in whose earth it was found, but this was in Libya – a country under the control of Muammar Gaddafi. Unsurprisingly, it was received by Gadaffi’s authorities, sequestered in a tiny building away from public view, and is now presumed lost. It is inarguable that this doesn’t benefit the Libyan people, the Italian people – from whose culture it came regardless of geography – nor anyone else. As H L Mencken said, “For every complex problem there is a simple answer – and it’s wrong.”

The Acropolis Museum

The previous museum used to be located on the Acropolis itself, but subsequent excavations necessitated a larger structure. After much planning and a few false starts, a new museum opened in 2009 just at the bottom of the hill. There are some criticisms of the building itself, especially its contemporary look despite its historical setting and role. I understand – I feel little love for architectural movements after 1929. However, the interior plan more than makes up for it, doing more than display the many treasures found on the Acropolis – it amplifies, celebrates, and illuminates both the importance of the site and the hopes for the future of its preservation.

Upon entrance, the spacious foyer allows for groups large and small to collect themselves and enjoy the requisite creature comforts. Nothing feels rushed, and the initial ascent into the first galleries are along a wide, gradual slope, which was designed to replicate the dimensions of the ascent to the acropolis itself.

All along both sides are very large display cases with an assortment of pottery, statuettes and other small artifacts, arranged chronologically. It is a good introduction to the scope of history represented throughout the rest of the museum.

The museum seems to have been designed with the postmodern sensibilities of freedom of choice and a celebration of multiple perspectives. This is quite literally seen in the flow from level to level and room to room, where one might approach a major display from underneath or behind it, and turn halfway on the approach to be surprised by another impressive display facing them from overhead. The revelation of new experiences just around corners, encouragement to explore in a non-linear, wandering fashion, and groupings of artifacts with their corresponding models, diagrams, and reconstructions, adds up to an endlessly engaging self-guided tour.

While I enjoy the aesthetics of more traditional architecture, the range of shapes, open spaces, and support systems available with contemporary methods and materials permits the variety and drama of the effects. The only other museum I have toured that achieves similar results is the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence, Italy, and I suspect (though I have not found the link) that the designers of both institutions were trained in the same thinking.

There are numerous other examples where the idea unfolds as you move through the galleries. For the Erectheon, a small architectural model shows the entire structure and its composite design, while a miniature dedicated to just the frieze showcases the narrative as it proceeds around the building. The display of the original fragments can then be understood with greater clarity, before you turn to enter an area surrounded by half-height glass walls allowing views from both the story above and below. You sense the importance of the space at the same time that your realize that you are approaching the Caryatids from the back.

The walk toward the front of the display builds the excitement as the acoustics change from the low-ceiling of the previous gallery into a much more open space. You are free to pause, circle, examine from every angle the objects, huge and impressive. In contrast to the experience on the Acropolis itself of being roped off several yards from the Erectheon building, you feel like you are now receiving a special privilege. Here is your chance to see the very finest things from the building, set up just for you, to ponder from any angle you please.

An entire section of the museum is dedicated to a different type of context – the recreation of polychromed statues. After seeing the ostentatious and substandard recreations crowed into the Greek section at The Met in New York, this was a welcome change. The displays here in Athens were scholarly and thorough, yet restrained, and grounded in well-documented evidence. The verdict is still out on what the polychrome looked like the day it was completed. Fortunately, in contrast to recent attempts to disparage the skill and sensibilities of the ancients, these displays honored and illuminated them.

The arrangement of the museum reserves the most important for last – the Parthenon. With a cheeky bit of bravado, the anteroom is quite modest, small, and frankly unappealing, except for its lone feature – two facing displays of very good scale reconstructions of the pediments flanking the side walls. The only drawback, selfishly, was that with so many people passing through, it was hard to get suitable photos without reflections.

The cramped entrance is worth it, because it opens abruptly onto a massive chamber, and you quickly realize the magic of the arrangement. You have walked out from the middle this time, and you turn to look up and see the grand procession of the Parthenon Frieze, full scale, right in front of you. Not skyed dozens of feet in the air, but within easy sight. Yet the overall lateral dimensions are still huge, as every panel is set side by side in the same monumental arrangement as on the original building. This gallery takes some time to take in.

The space is ample, with exterior glass up to the ceiling to permit a grand vista onto the very building where these treasures once lived, and plenty of seating for quiet contemplation. The walkways permit large groups to stop at will, and the courses of artifacts are separated enough in height and depth that you want to walk around the entire room multiple times.

Many of the pieces are very eroded, and many are replicas, evidence of the philistine Morosini’s guns. Thwarted by his own ineptitude, he was the first to fail plundering the Parthenon sculptures. Elgin proved luckier, perhaps because his original intentions were nobler as an archivist. However, after the greedy Phillip Hunt despoiled as much as he dared, Elgin oversaw their removal and transport to Britain. Greece was caught in the middle of foreign interests, and the damage was permanent. Hopefully, the loss can someday be amended in part by the return of the art.

In this grand gallery, their absence is painfully felt, and it is entirely intentional and dare I say, welcome. The political dimension of this new museum was for Greece to show the world that it had the space to properly preserve and display the full appointment of artifacts. Today, it feels like the Elgin Marbles are lost children, and Athens has made up their beds waiting to welcome them home.

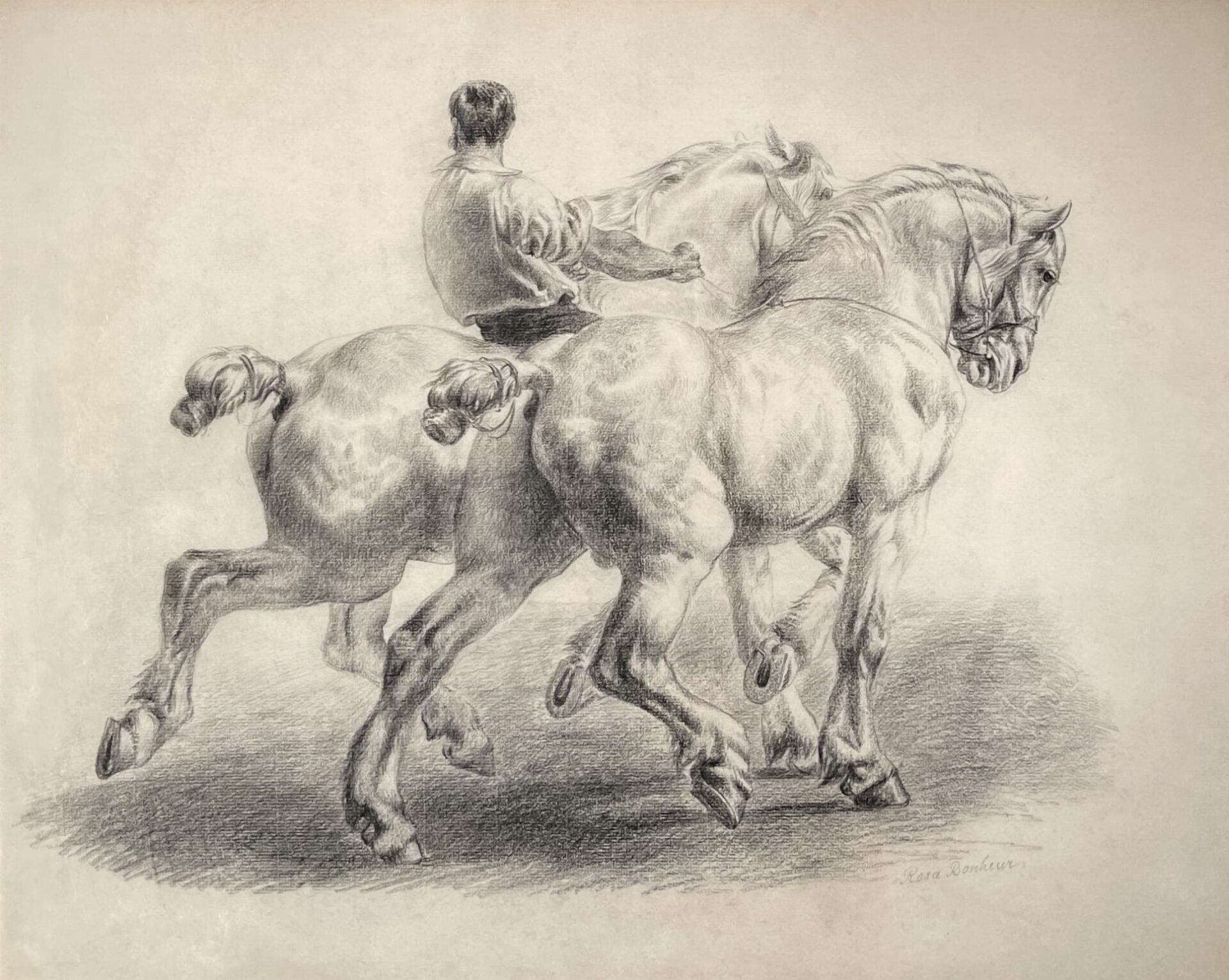

Yet, for all of this, there are moments of incredible beauty and sensitivity throughout the remnants. Gauzy, flowing fabrics, majestic horses galloping in formation, and the fitness of the poses and scales of the figures into the geometric scheme. Despite its fragmentary nature and massive scale, you can get some sense of the incredible achievement that was the Parthenon.

In the next article, we will continue our exploration of Athens with the National Archaeological Museum, The Ancient Agora, and the Kotsanas Museum of Ancient Technology.

Leave a Reply